"India to me, it was primitive, interesting, and I'm like Kipling: 'East is East and West is West, and ne'er the twain will meet.' And I lived there twenty-eight years."

-Kate Garrod, whose husband was an engineer in the Indian Public Works Department

Never the Twain? Indo-British Relations

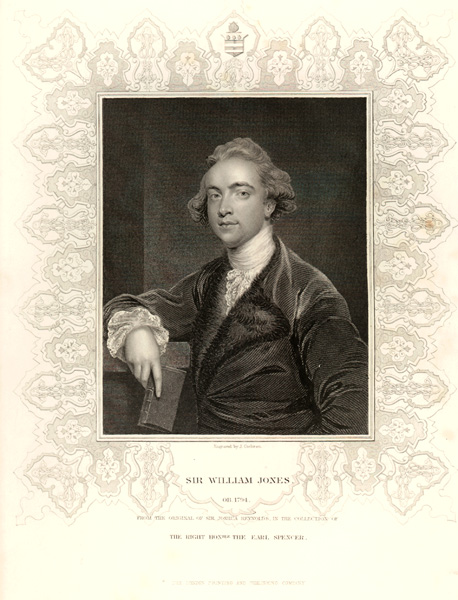

The nature of relations between the British and Indians changed over time, as did British attitudes toward India and Indians. In earlier days some Britons assimilated readily to Oriental ways of life or even intermarried with Indians. Particularly after the traumatic uprising of 1857-58, however, relations were often strained, as conventional ideas about European racial superiority became more prominent and as Victorian notions of morality and evangelical movements to convert the world to a particular kind of Christianity became influential. By the latter part of the 19th century, for example, the idea of a "respectable" English person marrying an Indian was virtually unthinkable. Of course, the very fact that the British were by definition a ruling elite and Indians -- however rich or important -- a subject people often strained relation. This could exacerbate cultural misunderstandings, a situation which is the focus of E.M. Forster's great anti-imperial novel, A Passage to India.

Those who remembered their time in India were aware that the Indo-British relationship was often problematic. They felt, for example, that a certain need to be impartial outsiders in the administration of Indian matters sometimes made them seem aloof. Yet they insisted that they frequently had cordial relations with Indians and were in close contact with many aspects of Indian life and society. They spoke Indian languages and, if touring a district, might interact with no one but Indians for weeks or months at a time. As time went on there was also increasing emphasis on Indianization of the various British services, so that more Indians came to have responsible positions that made them officially equal or even superior to Englishmen in the administrative systems.

Constraints in social relations sometimes meant that Britons interacted with Indians mostly in formal or superficial situations.

In their taped recollections Britons spoke with particular affection of encounters with Indian peasants and other common folk. Of course there was no question of peasants claiming social equality with European sahibs, so they in no way impinged on British dominance and could even be romanticized.

On the other hand, interviewees suggested they had limited intercourse with educated, middle class Indians -- who increasingly challenged British rule as time went on -- and some indicated ambivalence about or suspicion toward such people.

Socializing with Indian princes was a high point of life in India according to many recollections. Connections to this world of royalty could validate British status.

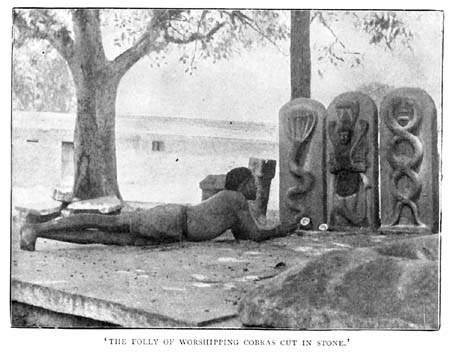

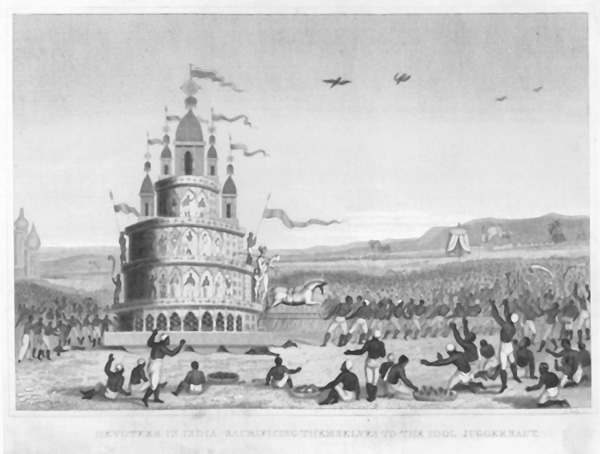

British attitudes toward Indian culture were complex. A few English people became devoted students of it, some had little interest in or were even appalled by it, others took a selective interest. Guinness's travel account was meant to champion the work of Christian missionaries and thus to denigrate Indian "paganism". However, in general interest in Indian customs sometimes focussed on those which were disquieting to Europeans. There was considerable fascination with the practice of "suttee," the immolation of widows on the funeral pyres of their husbands, a practice finally outlawed.

And there were many accounts of the Jaganath procession, in which the Hindu deity was pulled on a cart by devotees, some of whom were crushed beneath it in an excess of religious fervor. Such customs could serve to suggest fanaticism, social instability, and the continuing need for British rule to control such excesses.

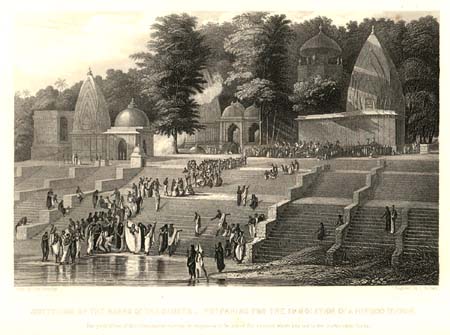

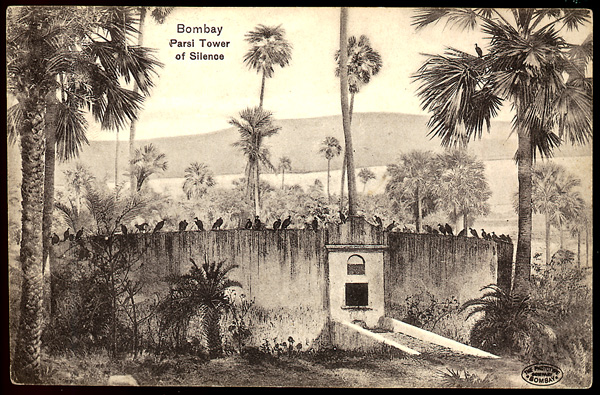

"Exotic," and to Europeans perhaps horrifying, Indian modes of disposing of the dead -- such as the Hindu practice of public immolation and the Parsi custom of exposing the bodies to be eaten by birds -- intrigued the British.

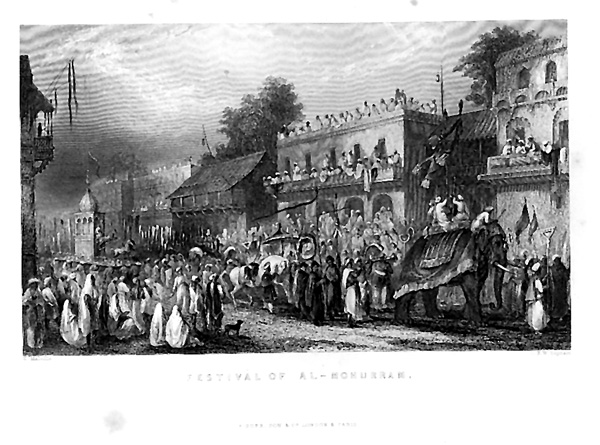

Though recorded because they seemed colorful, images of sectarian festivals were also reminders that these customs could provoke violence between Hindus and Muslims and that British rule staved off intercommunal chaos.

First published in 1868, this pioneering collection of oral tales is indicative of the interest taken by some English people in Indian culture through folklore. Frere was the daughter of a Governor of Bombay.

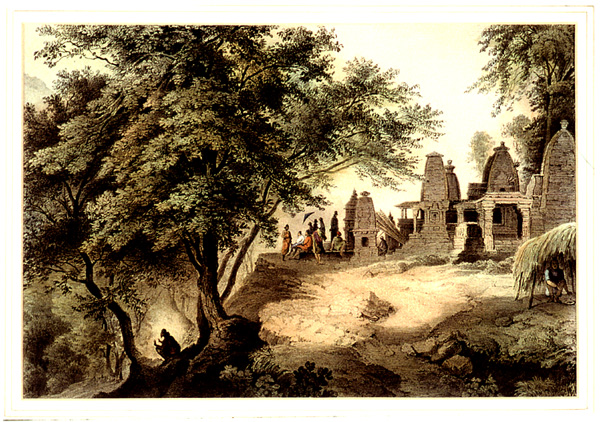

Indian architectural splendors attracted British and other Western visitors. Prince Waldemar, a talented amateur artist, was one of a number of distinguished Europeans who visited British India for sightseeing or sport.